A quick guide to China's changing monetary tactics

By Alaistair Chan- China’s evolving financial system has required the central bank to change its tools.

- Capital outflows and the gradual liberalization of the yuan mean that the era of sterilized intervention is ending.

- A new governor could move the PBoC towards a more conventional market-based policy, although the overall policy stance is still expected to be set by the government for the foreseeable future.

Monetary policy in China has traditionally had three levers: interest rates, reserve ratios and the currency. The State Council (made up of the premier, vice premiers, and heads of various government departments, including the central bank) decides on lending and deposit rates, while the People's Bank of China has discretion over commercial bank reserve ratios. Each can influence policy on the currency, although the State Council has the final say.

Reserve ratios are falling out of favour as a macroeconomic management tool. They were last adjusted in May and have since stayed at 20% for big banks, despite an economic slowdown in the following months. Reserve ratios have remained stable because they perform double duty. Along with managing liquidity in the banking sector they also restrain liquidity arising from the PBoC’s sterilized interventions and reduce the impact of nonperforming loans.

What is sterilized intervention?

To manage China’s currency peg, the PBoC buys and sells yuan and dollars to keep the exchange rate within a certain range of its daily fixing rate. In the past few years this has meant printing yuan to purchase dollars from exporters and commercial banks, while issuing equivalent amounts of yuan-denominated bonds to keep the domestic money supply stable, a process known as sterilized intervention. The dollars are added to the PBoC’s foreign exchange reserves, which rose to US$3.3 trillion in September 2012.

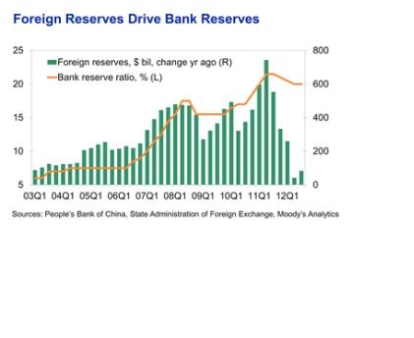

To boost demand for the yuan-denominated bonds the PBoC has raised reserve ratios at banks, in effect forcing banks to buy the securities. Partly for this reason, reserve ratios for big banks track changes in China’s official foreign reserves quite closely. The reserve ratio for big banks rose to a record 21.5% in June 2011, the same month that official foreign reserves were up $743 billion from a year earlier, the biggest increase on record.

See Figure 1.

However, for most of 2012 there has been a disconnect between flat foreign reserves (which even fell in the second quarter) and relatively high reserve ratios. This is because sterilized intervention has become less necessary, partly because of the gradual liberalization of the currency and also because of capital outflows. In April the PBoC doubled the trading range of the yuan to 1% aboveor below the daily fixing rate. As 2012 progressed the PBoC reduced its activity in the market, nudging the yuan up or down only when it hit the upper or lower bounds. Instead it sought to take its cues from the market, albeit slowly.

See Figure 2.

In midyear as interest rates were cut twice and capital outflows intensified the PBoC stepped in to prop up the yuan, which traded at the lower end of its allowable range, and also guided the fixing rate lower. This has since reversed as economic conditions improved, and the yuan is now trading at the top end of its allowable range. The wider trading range means that there is less need for the PBoC to intervene in the market, and capital outflows mean that some of the interventions were to prop up the yuan's value rather than to lower it, both of which lessened foreign reserve growth and hence the need for sterilised intervention this year.

Liquidity shortages

Capital outflows may have contributed to reports of liquidity shortages at some Chinese firms and added another wrinkle to China's monetary policy. In theory, the situation could be alleviated by simply reversing the sterilized intervention process: sell dollar assets and use the proceeds to buy back yuan-denominated bonds, thus releasing yuan into the economy. However, the situation is complicated because close to a third (or around $1.2 trillion) of China’s reserves are in U.S. Treasuries. In theory this is the most liquid part of China's foreign reserves, but in reality any large sales could prompt market panic, or at least cause a substantial loss in the rest of China's Treasury portfolio.

Hence the PBoC has been relying on reverse repo operations to manage domestic liquidity. Reverse repo operations are open market operations in which the PBoC injects or withdraws money from the banking sector and wider economy by buying and selling short-term(seven-day, 14-day and 28-day maturity) securities.

See Figure 3.

Over the past six months the PBoC has greatly expanded its reverse repo operations. Its weekly announcements of total operations have moved markets as they (supposedly) indicate whether an interest rate or reserve ratio cut is imminent. A rising amount of reverse repo operations implies greater liquidity and lowers expectations of reserve ratio cuts. In our view, it is increasingly likely that the purpose of bank reserve ratios will change to that of developed economies: as a buffer against the risk of insolvency. As such, reserve ratios in the future are likely to be set in accordance with international standards such as the Basel regulatory framework.

A changing lineup

The current PBoC governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, is due to retire and speculation on his replacement has narrowed to Shang Fulin, head of China Banking Regulatory Commission, and Guo Shuqing, head of the China Securities Regulatory Commission. The emphasis on regulatory experience is an indication that upcoming changes are likely to be regulatory based, such as improving market input in interest rates and the currency, rather than a shift in scope towards a more developed monetary policy. In this regard, given that benchmark interest rates are set by the State Council, the PBoC is likely to rely on its own tools, such as open market operations, more heavily. A corollary of this is that the central bank will continue to implement the government's policy, rather than set it.

Advertise

Advertise